Tuesday, August 31, 2004

Ancient genetics

The moa were a class of massive ratite birds that lived in

Although a great number of very complete moa skeletons have been discovered classifying these remains into discrete species has proved something of a challenge. At one stage as many as 64 species comprising 20 genera were accepted, while modern taxonomists prefer a total of 11 species. Last year a team of researchers from

The international team focused on the largest of the moa, the genus Dinornis. Differences in skull shape and vertebrate structure distinguish this genus from other moa specimens. Specimens within the genus differ wildly in size with biologists classifying Dinornis bones corresponding to birds varying between one and two metres in height and 34 and 242 kilograms in weight.

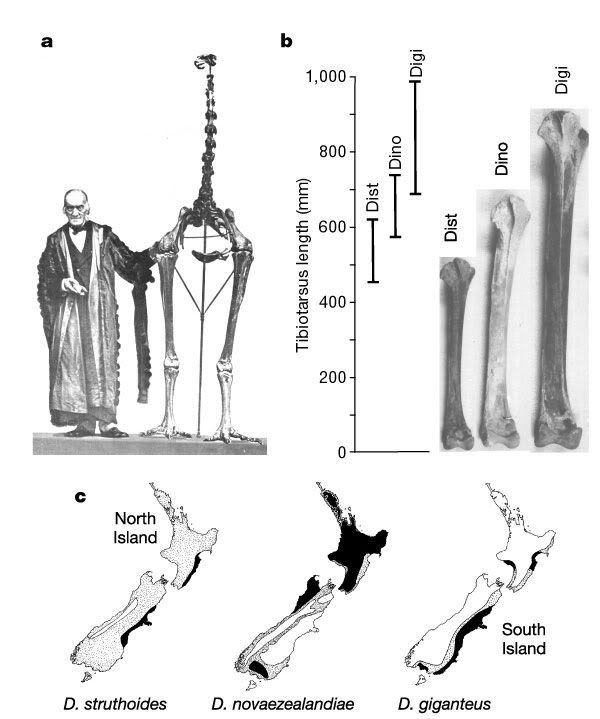

a, Naturalist Richard Owen holding the fossil femur fragment used to predict the existence of the moa in New Zealand. The skeleton is from D. novaezealandiae. b, Size comparison of the tibiotarsus bone of the three Dinornis species. The partly overlapping size ranges illustrate the extent of variation in tibiotarsus length within each of the Dinornis species. Digi, Dino and Dist refer to D. giganteus, D. novaezealandiae and D. struthoides, respectively. c. Distribution of Dinornis Holocene palaeontological records within the North Island and South Island of New Zealand. Shading indicates prominence of species in fauna: black, prominent; stippled, regularly present; unshaded, rarely, if ever present. (image and text adapted from Cooper, A et al, Extreme reversed sexual size dimorphism in the extinct New Zealand moa Dinornis, Nature 425, 172 - 175

There are a number of ways that the discrepancy in the massive difference in size between specimens and the relative genetic consistency can be explained. The most obvious is that the different skeletons were actually a mix of adult and infant birds, this can be discarded because other features of all the skeletons show them to be adult specimens. Alternatively the skeletons could represent an evolutionary timeline in which either very quick growth or dwarfing is being exhibited. Again it seems reasonable to discard this explanation as all the skeletons looked at by the researchers can be shown to be between 1000 and 4000 years old, not long enough for these massive differences to occur.

With no good explanation for their observation of homogenous DNA sequences across such wildly different skeletons the researchers decided to investigate whether there was a correlation between the size of a skeleton and the sex of that skeleton. Such “sexual dimorphisms” are common and the kiwi, a living relative of the moa, shows “reverse sexual dimorphism” were females are larger than their male counterparts.

Birds have sex determining chromosomes much like the familiar X and Y system found in mammals; a male bird has a ZZ make up and a female ZW. (Sex determination is actually an interesting topic in its on right and one I hope to cover at some stage.) To test whether a DNA sample represents a female bird DNA samples are screened for DNA sequences specific for the W chromosome and at the same time a positive control, a gene known to be found in the species in question. If a sample can be shown to have W-specific sequence it is female, if it has the positive control and not the W-septic sequence it is male and if it has neither sequence then the recovered DNA was probably not complete enough to get a solid result. The moa samples were sexed using a modification of a method designed for the related kiwi. The results showed that what were considered the two larger species, D. giganteus and D. novaezealandiae are in fact all females while the smaller D. struthoides are males. From this data the researchers concluded that the genus Dinornis is in fact one species exhibiting the most extreme reverse sexual dimorphism known in vertebrates, with the largest females about 150% the height and 280% weight of the largest males.

Re-examining the data with this break through in mind further supports the sexual dimorphism hypothesis. Once D. giganteus and D. novaezealandiae are considered females of one species the ratio of female to male remains in the swamps from which moa bones are found prove to be very close to the 1:1.44 that is the average for modern ratite birds. In birds reverse sexual dimorphism is related to investment in the production of eggs, so this insight may show us something about the behaviour of a now extinct species.

The study may also provide something of a salutary lesson to taxonomists and archaeologists keen to classify organisms based on very small samples. Often entire organisms area classified largely on one or two bones. Here very many complete skeletons of a recently extinct animal couldn't be used to correctly classify the genus Dinornis. Alan Cooper, a researcher on he project sums up his concerns:

We have thousands of bones [but even with that] record we could not work out we were looking at different sexes of one species. What does that say about our ability to study… ancient human groups where you’ve got one ankle bone and a bit of a tooth?”

(Links to abstract and full article)